Aisling Conroy- PRISM @ The Talbot Gallery 7th-30th March 2013

Essay by Marie Soffe (BA, MA)![]()

As a fellow student of fine art in NCAD, I was always amazed at the single-minded focus of Aisling Conroy’s practice. She was, and still is, a prodigious worker with a prolific output, her vivid imagination finding expression in an abundance of mediums which she mastered easily – drawing, screen-printing, etching, animation, sound, and sculpture – many combined in fascinating dioramas constructed with skill and attention to detail. Her impressive portfolio of practical and artistic skills has ensured that every piece is crafted with her unique combination of quality and conceptual depth, something that has not been lost on her many discerning collectors.

The exact and intricate drawing that was a feature of Conroy’s student prints, together with the psychologically intense three-dimensional scenarios, all point to her previous training in Animation Production. Whilst not immediately apparent in her more recent work, this training actually underpins it in a vital way, as evidenced by the well-considered and meticulous combination of sound, sculpture, image and process that comes together in this visually and conceptually rigorous exhibition, Prism.

Colour has always been present in Conroy’s work, subtly in her etchings and screenprints, more dramatically in her dioramas, animations and digital prints. However, two expeditions in recent years have had a profound influence on how she now gives form to her artistic concerns: firstly a trip to South America and then an extended exploration of India. These periods of travel exposed her to the vibrant and vivid use of colour in both cultures and awakened a sensitivity to the powerful potential of colour, light and sound to affect the human psyche in unexpected ways. This has led to a dramatic paring down of expression. From the terrifying birds and other imaginary creatures that populated her earlier prints, Conroy has moved to a distillation of her artistic vocabulary into a simple, well-defined set of parameters: pure colour, pure light, and layers of gentle, mesmerizing sound.

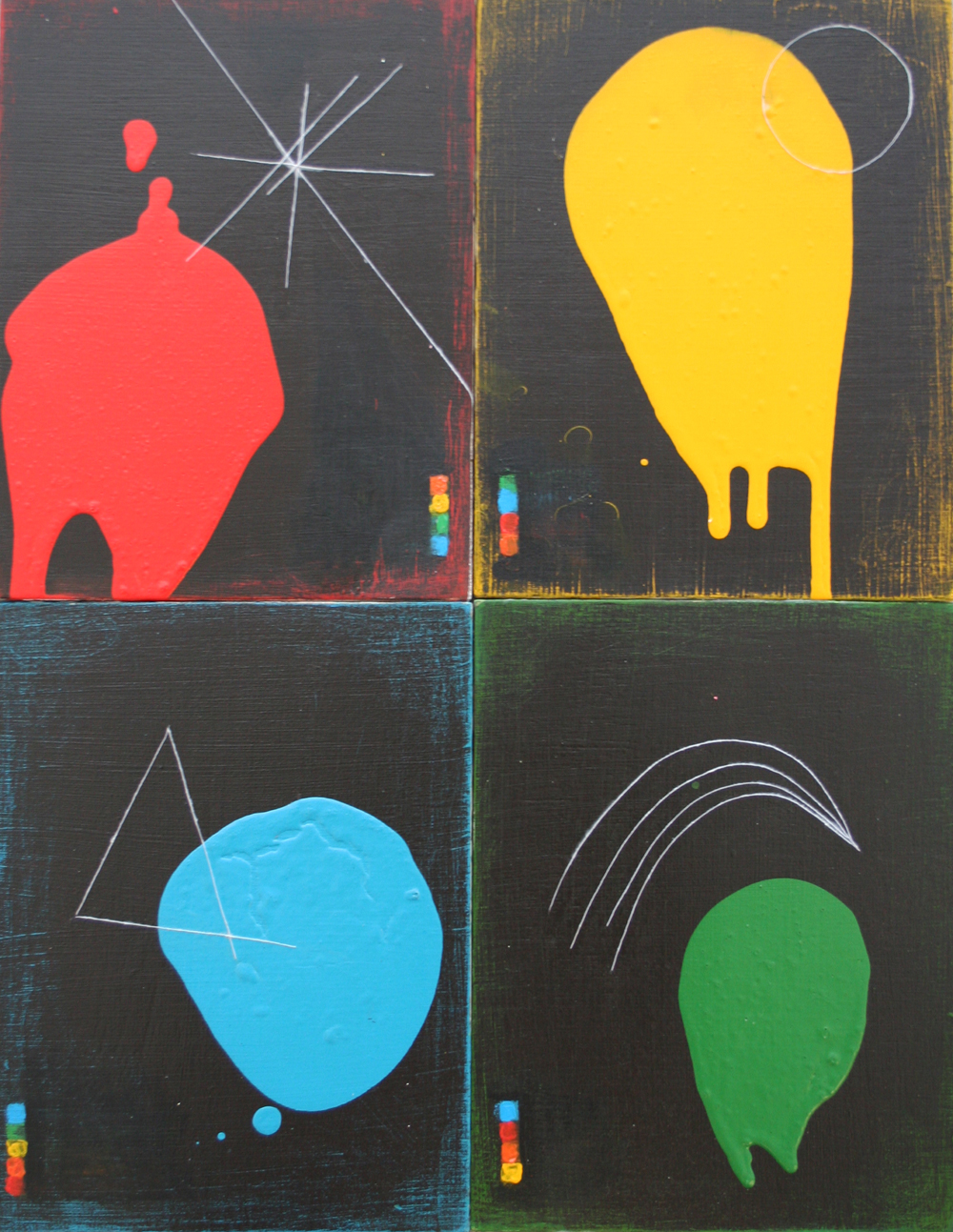

In this exhibition, these elements have emerged in a unified series of small, icon-like paintings on wood, some cardboard assemblages of rectangles and circles, their vivid primary colours immediately evoking the works of Mondrian, and a rainbow of light refracted through a triangular prism, coupled with one of Conroy’s signature void sculptures incorporating a layered sound installation.

The word ‘icon’ is important as it encapsulates the full breadth of what Conroy is attempting to achieve in this work. Derived from the Greek eikon, meaning ‘image’, the icon is traditionally a religious work of art, usually a small flat panel painting used in Eastern Christian traditions, which uses strict symbolic codes to show complex ideas in a very simple way and to draw the viewer into contemplation of the divine. The icon is a signifier of someone or something sacred – a saint or the cross, for example – and thus it alludes to the signified rather than being a representation of them. This concept of signification is inherent in Conroy’s use of colour and the icon’s physical format to allude to a particular psychological state rather than illustrate it. She attempts to draw the viewer into a calm and meditative condition such as is induced by exposure to the sublime, her idea of the sublime being that unexpected experience of surrender brought on by the diffusion of light through a stained glass window, the deep silence of an ancient temple, or the repetitive sound of chanted prayer.

Conroy’s cumulative process in producing these works echoes her intention for them. A slow, deliberate pouring of paint results in amorphous concentrations of colour on either white or black grounds. Careful ‘drawings’ with thread, inspired by John Cage’s scores, form tangible motifs such as triangles, squares, circles, or spirals, recalling the ‘Renaissance triangle’ and other mathematical forms utilised by the Renaissance masters in their religious paintings. The triangle was also used to sublime effect in Andrei Rublev’s icon of the Trinity in the 15th century, probably the world’s most famous icon and a work which is rich in the symbolism of colour and form.

As artists who seek to evoke the sublime, Conroy is inspired also by Anish Kapoor, who has used the rich pigments of his native India in many of his seductive and monumental works, and by Olafur Eliasson, a creator of fully immersive light and atmospheric installations. In contrast, Conroy’s work is quiet, requiring a generosity of attention from the viewer, both visually and aurally. It yields its rewards, like the icon, after contemplation of its symbolic language and a subtle reading of its vocabulary of shapes. Through the prism of their personal experience, each viewer will arrive at their own translation.

Marie Soffe