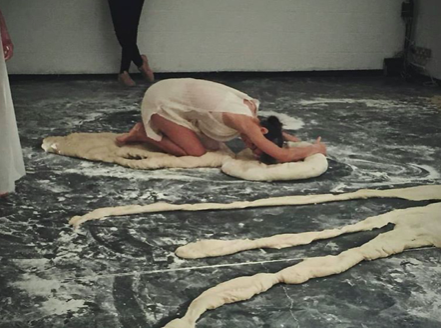

Six contorted, heaving bodies, six mounds of dough, arms and legs entwined with lengths of proved flour, yeast and water. Twisting, manipulating limbs and torsos. Cold, thick slaps of bread dough against concrete. Brushing of feet and fingers, the clatter of elbows, palms and kneecaps against the flour sifted floor. Dusty sweeping of limbs. Panting fury. Laboured breaths. Exhausted sighs. Groans of resistance; of perseverance. Our bodies; our battleground.

Emma Brennan’s authored durational performance “Heed, to the Mound”, presents a group of women negotiating space through the movement of mounds of bread dough within the space of The Complex for Dublin’s 2018 Fringe Festival. Taking place over the course of 3 hours, physical exertion takes it’s toll on the performers as they use their bodies to manoeuvre and manipulate mounds of bread dough, equivalent to the weight of their own bodies, across the performance space. Heed brings to the fore the question of space, how it is occupied, who occupies it and how we negotiate our bodies accordingly. Moving mounds through the tumultuous terrain of gender politics proves no easy feat, as the excruciating and exhaustive work quite fittingly erodes these women mentally and physically throughout the duration of the performance. With puffed red faces and sweat glistened necks, the performers roll, twist, knead, push and pull their dough with ferocious determination evoking an emotional response from spectators. As tightly clenched fists punch into dough and miniature mountains inch across concrete we see the slow progression of women’s rights throughout history, we see the everyday instances of aggression and violence toward female bodies, we hear the hurt and fury in the exasperated groans of women on the battleground of Ireland’s sociopolitical landscape.

The undervaluing of women’s labour throughout history and the unseen emotional labour expected of women within contemporary society are brought to the fore in Heed. Taking inspiration from her grandmother’s tradition of baking brown bread for the family, Brennan questions the devaluation of homemaking skills, deemed as “women’s work”, in Irish society. In rural Irish homesteads, the process of baking seemed to go almost unacknowledged and undervalued compared to the work of men’s labour on the farm or outside of the home. Heed, to the Mound points a finger at society’s valuation of the workload associated with the traditional role of the homemaker. Through the poignant actions of a group of women labouring intensively, exhausting every part of their bodies, over masses of dough, attention is drawn to the intensity of this work and respect that must be commanded of the act of making. Heed emphasises the importance of valuing these acts of unseen and undervalued labour in opposition to the emphasis placed on working for monetary gain within a capitalist system.

Brennan refers to her process of preparing the dough as a metaphor for the creation of life. “With flour and water, we can create a living, breathing body, something which can grow through proofing.” The genderless, sexless, mounds of dough present each performer with an opportunity to experience a sense of self without the weight of gender bias, stigma, discrimination, fear or insecurity. With pressed backs, stomping feet and curled fingers these women manipulate their very being across a public platform. Each women tending to their own projected doughy selves; some rip chunks out and squeeze together again, some stretch and roll out for lengths becoming thinner and thinner with each inch, some repeat the pulling and folding of flaps; the slapping of flesh and dough reverberating through the room. When kneading dough you cannot be heavy-handed – it changes the entire consistency and texture, you can taste a bread baked with love or anger. A handful of dough receiving the blunt force, or gentle caress, of emotion; do our bodies receive the same attention from the space we inhabit? Politics are a tactile experience, and the daily micro-aggressive touch of our oppressive sociopolitical sphere lingers in our physicality and psyche alike.

The socio-political landscape of contemporary Ireland has been aflood with dissent regarding the relationship between the state and women’s bodies. In 2018, Irish society saw the culmination of decades of protest in the passing of the movement to repeal the 8th Amendment from the Irish constitution. The year also marks the centenary of women’s partial suffrage in Ireland; 1918 was the first time Irish women (aged 30 or older who were university graduates or owned a certain amount of property) were permitted by law to vote and run in parliamentary elections. Both movements saw women collectively struggling against structures of power that sought to oppress and define them physically, mentally, socially and politically. From the violent beatings of protesting suffragettes at the hands of police forces to the vice grip of the 8th Amendment and the mobilisation of women in the campaign to repeal it, the female body indefinitely exists as a site of conflict in a constant struggle against its aggressive politicisation. Taking place just three months after the referendum on the 8th amendment was held, Heed, to the Mound allows for a form of post-repeal conflict resolution to play out on the concrete floor of The Complex. The struggle of dissent against patriarchal structures of power echoes through the space as violent slaps of an elongated limb of dough reverberate through the concrete floor. Forcefully, in spite of her evident fatigue, a woman thrusts it behind her shoulder to gain momentum before hurtling it down upon the flour scattered ground. Some of the dough breaks away to hit a nearby wall. She repeats her action; the dough catches her behind the neck with a smack to her upper back; there can be no disruption without trauma. She perseveres.

Exhausted, and seemingly close to defeat, one woman halts her movements. The mass she had been inching across the space has begun to stick to the undredged floor and each push is met with increased resistance. As she heaves her body upon the mound to catch her breath and rest for a moment, she is spotted by the human dredger. This woman stands watching over the others, smiling gently, a mountain of flour in hand. Upon seeing distress, she tends to the struggling womens needs by sifting flour with great care around the stubborn masses of dough. A moment later, the performer is moving again. In times of mass dissent against oppressive forces of power, it is collectivity and care for ourselves and one another that carry us through. We must remember to pay heed to the mound.